Listen to the Fiddle Studio Podcast on Apple or on Spotify!

Welcome to the Fiddle Studio Podcast featuring tunes and stories from the world of traditional music and fiddling. I'm Meg Wobus Beller and today I'll be bringing you a setting of the Birds from a session at the Art House Bar in Baltimore, Maryland. Hello everyone, happy New Year. I hope you are well. Today. Our topic is the biggest mistake I see this month. I'm working on a course for how to play the fiddle faster and this is part of it. One of the areas of the course will also be the subject of this podcast.

00:55

When I started this podcast it was last fall I was also working on a lot of filming videos for how to learn the fiddle. Why was I filming all these videos? Well, I taught fiddle and violin Suzuki violin for 20 years and I learned a lot at that time about teaching, about violin, about fiddle and fiddling and teaching fiddle. I've recently reduced my teaching load. I don't teach a lot anymore here. I don't have my own big studio of kids anymore, but I didn't really want to walk away from all of that and that part of my life. I did do a lot of filming and I wasn't quite sure at first what to do with the videos whether to just put them on YouTube. What I ended up doing was putting them, organizing them into courses and putting them on a website so that people could take them as courses, buy them and then use them. I had intended to keep creating more courses and put one up basically every quarter. I will say last year my album and some of my writing got in the way of that. It's nice to be diving back into filming. I have a great plan for this course. I have time set aside next week to film it and it should be out in February.

02:25

A lot of different ways to practice playing faster, and some of them you might expect and some of them you probably wouldn't. For today, the biggest mistake I see. As I said, I no longer teach full time but I can't quite lose my teacher eyes, which isn't to say that if we play together I'll be judging you, but I do notice what's happening with people's playing because I for many, many years, six hours a day, I was training myself to notice what was happening with people's playing and think about it. So this is going to be about the right hand, the bow hand. There are a lot of issues with left hands. I see all different kinds of things, usually what people could work on more is kind of unlocking and developing some softness and flexibility to move the fingers around, and that's actually going to be one of our topics later this month. But the biggest mistake I see is people using too much bow, more than they can control. It's a little bit about keeping your bow straight. It's a little bit about the grip on the string, the contact point, but it's also just about not using more bow than you can control. It's funny.

03:52

My family has been watching Star Trek, the next generation, and of course, Data, the Android character, plays the violin, and so there's these episodes where Data plays the violin. He's doing these big long movements with his right arm. I mean it's really terrible. It doesn't look like they gave the actor any help at all to try to look realistic. In fact, sometimes they just film him from behind or someplace where you can't see quite how ridiculous the impression of violin playing looks. My kids enjoyed that because they could see how bad it was. The thing that I did notice was that he's doing these long movements with his right arm. They don't ask anyone on the street. You know what's the motion for playing the violin. They'll draw out these lines with their right hand, they'll move their arm back and forth, and that's what everyone thinks of, and those big arm movements are really the hardest thing to play with a violin. A good tone to really grab the string and keep a firm grip on it all the way while your arm moves farther and farther away from the string and then changes directions, even keeping your your hold on the string there, but not too much of a hold, or you'll crunch and then bring your arm all the way back in towards the string, and having a firm contact point the whole time Working on long bows is how you work on your tone.

05:27

When people say to me why really want a really good, clear tone, like a classical player, or they'll give me names of fiddlers who have a really beautiful tone. Sometimes they have classical Training and I tell them it's not reels and jigs that gives you that tone. It's playing slowly, so whether it's classical waltzes, airs, it's using a lot of bow and learning to control it. But when you're playing a tune up to speed, you only want to use as much bow as you can control so that your bows staying completely straight, it's not moving around on the string, so that you're not getting that bow to string noise entering in with your tone and it also affects how rhythmically you can play. This is also something where I'll see people who's left and right hands aren't that coordinated and it makes their playing sound messy and it's usually because they're using too much bow. So you want to use really small bows trying to play a real or a jig up to speed At home.

06:37

If you're learning bow control, which is a whole area, you can go nuts experimenting with all kinds of things. Violin players will do like 30 second bows. You know one down bow for 30 seconds. I used to do like a tiny down bow at the frog and then move my bow in the air and do a tiny up bow at the tip and come back and forth and learn to do that rapidly, which requires quite a bit of control with your right arm. Repeated down bows and up bows, down, down, down, down, down, down, down, down, down. Getting that control that way. Slurring patterns are great for this, even just playing a scale with changing the amount of pressure speed you're using. Try everything at home. But when you're working on a tune, use less bow, use less and less until your contact point is very solid, your bow is very straight, the hands are coordinated and don't worry about using more until you know, until that's really really steady and really how you want it. So that's the biggest mistake I see is just people using a lot of bow who don't have that control.

07:51

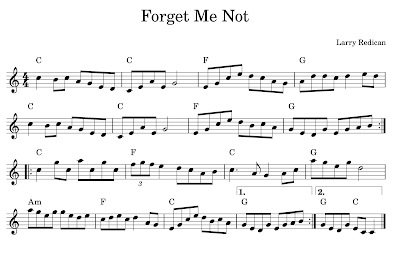

Yet Our tune for today is the birds. This is a hornpipe. I looked it up on the session wasn't the most useful set of comments. There were a lot of people just making bird jokes and then there were people complaining about the bird jokes. It was entertaining. It wasn't that informative. There was a post from Jimmy Keen who talked about recording this hornpipe with Mick Maloney. On the album there were roses and he says that Kevin Crawford learned it from that recording and a lot of other players and that he also liked to play it as a slow reel. He went on that the Galway box player, Sean McGlynn, liked playing it as a reel instead of a hornpipe. You know, some tunes are kind of flexible like that.

08:48

The tunes for this month will be Irish tunes and I pulled them off from a session I went to over the holidays with two brothers, Connor Hearn and Brendan Hearn, who play cello and guitar. They both play guitar. Connor's a great guitar player. Brendan plays cello and guitar and all the things and Dan Isaacson was there playing bagpipe. Dan plays bagpipe flute whistle has a very long history in Irish music, played in Boston and studied there, now plays in Baltimore and does a lot of leading of sessions around here and performing.

09:28

Charley and I were the only other folks there so we got to play and hear a lot of their tunes and lead some of our own tunes and it was fun. So the birds hornpipe is a tune I think. I think Connor played this on the banjo. It was played by Noel O'Donohue, a flute player from County Claire, also played by Hugh Healy. Somebody founded in the O'Neill's book as Jerry Dolly's and then it was recorded under that name by the Mulcahy family in their album Real and in Tradition and we're gonna do it now for you as a hornpipe. Here we go.