Welcome to the Fiddle Studio Podcast featuring tunes and stories from the world of traditional music and fiddling. I'm Meg Wobus Beller and today I'll be bringing you a setting of La Moquine by Claude Methe from a Jam at Fiddle Hell. Hello everyone, I hope you are well. Our topic today is Not All Notes Are Equal. I've been thinking about this topic a little bit, that in fiddle tunes different notes are played louder or quieter or more or less accented during fast passages. Trying to kind of get to the bottom of some of this in my brain, maybe because I'm transferring fiddle tunes to a different instrument with a concertina and trying to figure out how to make them sound like dance music. Part of it is the fact that not all notes are played equally loudly or accented in fiddle tunes, so it's very different. In classical music or even a lot of times in many kinds of singing, classical violin, there are dynamics. So dynamics is playing loud or playing soft, doing a crescendo getting louder, doing a day crescendo getting quieter. That's not really what I'm talking about. It does mean that those notes are not equal, but your tone, your sound kind of stays stable and beautiful and then you bring it up, you bring it down. You might try to find different colors in your tone, but you're not ever really in classical violin unless you're playing something fast, with accents, which is really imitating dance music. You're not playing passages and trying to make the notes different. You're trying to make them run smooth, whether it's all in the slur or it's all separate notes. You're not trying to make a lot of notes stand out in like a rhythmic, danceable way. It might be more about the phrase, the way that fiddlers do it, rather than these long crescendos and then playing loud and then getting very quiet. And playing quiet is that it's more like a percussion groove. So if you think about several percussionists playing together for Latin music or even one person playing on a drum set but it's several different kinds of drums and cymbals, some of the hits are going to be louder or softer or more accented or just have a different quality, and it's all of those together in a rhythmic pattern that makes it feel usually like dance music.

Dance music isn't all the same rhythm all the same way. It's a mix of things. And so you hear like the cowbell and you hear the congas and you hear the bongas, and it's the difference, but they're all together and they're moving rhythmically through this pattern Fiddling, playing a reel or a jig, a fast fiddle tune. We're trying to do that. We're trying to play different notes in different ways to make it sound dancey, like a rhythm, like a drum set playing a rhythm. The difference with classical violin might be more like somebody singing a song.

There's different kinds of singing in Irish music. Sometimes we have a singer at our session who does ballads. Her name is Catherine O'Kelly. She's a great ballad singer. She is focused on the shape and the words and the story but she's not trying to create a danceable rhythm with her voice. But there's another kind of singing in Irish music Lilting, where they're actually singing the fiddle tune using different syllables, trying to make it sound like dance music with their singing of it. They're Lilting, so I don't really scat, but it's a little bit like scatting and I'm not using the same syllable for every note. We actually do that in Jewish music. We go lie, lie, lie, lie, lie, lie, lie, lie, lie, lie, lie, lie, lie, lie, lie, lie, lie and it's all lie. But in Lilting you use a mix. Just like for fiddling, playing reels, playing jigs. You're using a mix of tones and attacks and dynamic and accented levels to give you that lilt in your fiddling, what I would do, because different styles have very different patterns and ways of doing this. I would say almost every traditional style that comes out of dancing for fiddle does this to some degree.

What I would suggest is, whether you're interested in Scandinavian or old time or French-Canadian or Irish, that you first go and listen to some fiddlers from that genre and try to hear it. Hear what is making it not sound like every note is the same, like a jig. An Irish fiddler doesn't play a jig (lilting) because usually the first note is more accented, louder, and I'm going mm. Because the second note is quiet. Some people ghost it, basically barely play it, and then ba, because it's sort of a medium note at the end. So that's just the way that I think about playing an Irish jig.

I would go, you know, listen to Brian Conway, listen to some fiddlers and see, even like see what syllables you might put to their tunes to kind of get a flavor of the mix of accented notes, ghosted notes. We go back to the example of the Latin band, like what the groove is, not the groove that the guitar player is playing although that can be helpful to sort of inform you on this journey but the literal groove of the notes that the fiddler is playing. You know, if you listen to Noah VanNorstrand play, there is a groove usually going on in his feet he's doing foot percussion and then there's a groove going on in the notes of his fiddle tunes so that the fiddle is being used partially as that percussive, like a drum set that can do these different accented notes and make it sound like dance music and not just like a lovely song. I grew up playing in New England and French-Canadian and they have a very syncopated (lilting). So you get a lot of unexpected notes punching out and so I love that, although I don't get to use the dissonant sound here. So how we play old time in Maryland, like I said, you can listen to the backup instruments to kind of hear the groove they're doing. But you can bring that into your playing a little bit. It's nice to hopefully your guitar player is also listening to what you're doing, bringing that into their groove, so you can get a nice synergy going there.

You can practice the groove if you're getting a sense of how you want it to sound. You can practice it on open strings or something really easy scales. I spent a lot of time practicing like I teach kids and adults little one string exercises ba-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da, and I get them ba-ba-ba-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da, or putting slurs in and before they try to put it into a tune to get that groove and just having them run up and down oh, one, two, three, four, three, two, one, oh, on every string, just getting it into their right arm on one string, without having all the string crossings and everything to deal with trying to remember a tune. So just on an open string or just with a really simple pattern on one string, getting your groove or your lilt going and then trying to push it into a tune. I actually would say you want like a pretty notey tune. Sometimes I'll use the Dancing Bear, this really repetitive New England tune by Bob McQuillen, because it's very easy and very notey. So if the tune has a lot of funky rhythms it might not be the best one to practice your groove on. You might want something with a lot of filled-in groups of three for a jig or a lot of filled-in groups of four for a reel. So that's a little bit about not all notes being equal. Hope that was helpful If you haven't thought about that before.

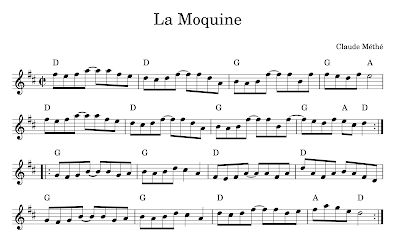

Our tune for today is another French tune. I don't know why I do this to myself with the pronunciation, but actually the tunes are so good that this is the hill I'm going to die on. I guess this tune is by Claude Methe. He is a singer, fiddler, collector of Quebecois music, travels around, plays a lot of traditional music and composes a lot of tunes and his tunes are very popular. This is a really fun kind of French-Canadian house party tune, La Moquine, and it is named for a fiddler named Elizabeth Moquine. I heard this at a jam.

I'll tell you this story. So this is what happened On the last night of Fiddler Hell. Charlie and I were playing. We left the concert a little bit early because I was actually just feeling really sleepy and it was like dark and with beautiful music and the concert and I was having trouble staying awake. So we left and we went to play a little bit of music and somebody else was playing some music had also left the concert.

There was another fiddling guitar playing and they were all the way up. They'd kind of gotten a spot away from us. They're in this stairwell, right at that sort of top floor, and the stairwell did sort of amplify what they were doing down so we could, even though they were sort of far away, we could hear them pretty well down on the first floor and they sounded really good. I was like I think that might be Lissa, Schneckenburger and Yann. So we ended up going At some point. I actually just put my instrument away for the night. My fingers were totally done and I didn't want to like be in pain or overdo things and I've been playing all day. So I was like I think I'm done for the day. I put my instrument away. We went up to listen to them a little bit.

Nicholas Williams came with the accordion and people were joining this little jam way up in the stairwell on the third floor. Down on the first floor they started organizing the big final night Scottish, cape Breton Irish. They had all these players. There was dozens and dozens of players playing all these Scottish and Cape Breton tunes. They were playing a lot of A and Lissa and Yann had been playing some tunes and some funky keys. So there's actually kind of a clash, like if you're standing in the right spot you're getting a lot of like A major C sharps in one ear and then from the smaller jam you're getting flats in the other ear. I think they could hear it down on the floor because they sort of started calling up like can you guys stop and just come join our jam? But instead of doing that, they just started picking more keys and more songs and playing them in F, which is a very clashy key with A, all of these tunes and funky keys and some Berkley kids came and it was a beautiful jam.

You can see it actually on if you go to like the Fiddle Hell Facebook group. Somebody posted a video and it's me and Charley and we're dancing to this tune that we're going to do La Moquine, which was the final tune they did before they actually did stop and just let the Cape Breton Scottish Fiddlers take over the soundscape. But that F jam was fun and maybe a little bit trying to tease the fiddlers playing an A. Some of it was definitely trying to tease them. Oh, they sounded so good. All those folks up in New England. I just love the way they played. So we're going to play this tune for you now, La Moquine, and I hope you enjoy it.

Next week is right around the Christmas holiday and I am going to be taking a week off, my first week. I think I've done 66 or 67 episodes in a row. I am going to replay a popular episode from about a year ago that I did about playing in tune. So next week will be a replay and I should be back in January with an interview with fiddler and banjo player Brad Kolodner that I'm very excited about and more topics. Thanks everyone. Thank you for listening. You can find the music for today's tune at fiddlestudio.com, along with my books, courses and membership for learning to fiddle. I'll be back next week with another tune for you. Have a wonderful day.